The late 1870’s are the most desperate of times for the Atherton family. Central Darwen either side of the main road is home to hundreds who slave day after day, hour after hour in the dark satanic mills of East Lancashire. Water Street and the area around it is the home of the Athertons until a breakout from the area in the 20th Century. In our cossetted lives it is difficult, impossible really, to fully comprehend what these people went through in those times.

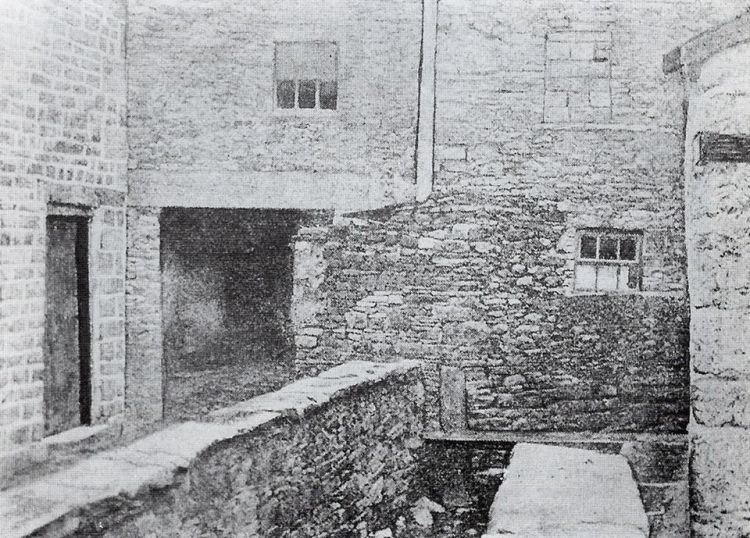

Water Street in Darwen was the lowest of the low, a virtual cess pit of squalor. Filth lines the winding streets and alleyways. At one point before the family moved upmarket into Water Street, they found themselves living just around the corner and the dwelling in this place was described as a ‘pod’ – one of three. It is difficult to establish exactly what this ‘pod’ consisted of, but I feel sure that Water Street despite its squalor was in fact a step up in quality – the pod would have been life in the most appalling conditions. This was a place of poverty beyond comprehension, an area populated by extremely large families, so large that the pitiful dwellings offered not an inch of privacy for the occupants. The narrow winding street was a running sewer that the neglected children had to use for their only space to play. The entrance door of the poorly built houses were raised up by a few stone steps just above the street – a means of at least keeping some of the water and sewage out of the living areas of the houses. Water Street was a part of Darwen that was notorious for its criminality. Brothels serviced the men of the area. Irresponsible men who continually got their women pregnant, producing children that had barely a chance of reaching school age let alone going on to adulthood.

Mary Atherton (Lowe), sister of my 2nd GGF has at least 13 children and as a mother she loses certainly a minimum of eight. In 1878 she gives birth to her final child Elizabeth. Then Mary expires, finally at rest. Her ravaged body is totally spent at the age of 42. She is not alone, this fate befalls so many of the women in the slums of Victorian England, and Darwen is counted among the worst of them all. The two men, my 2nd GGF John Atherton and his brother-in-law John Lowe, had without doubt a hard life. However, they do not put the interests of their wife and family first. Despite the dire circumstances of the times, it is difficult even from this distance in time to excuse the way they conducted themselves, although the mill system would have broken most men. John Low fathered as we know at least 13 children with his wife and John Atherton fathered at least 10. They had no realistic means of supporting such a large number. Living in the desperate area of Water Street this condemned their wives to a life of totally misery, not to mention what the children must have suffered in such poverty. One of John Atherton’s children, Jonathan, goes on to father eight children and only one of these survives to adulthood.

The area in and around Water Street would have been rife with syphilis and this would have weakened the children as well as their mothers. The mortality rate in this area of Darwen was off the scale and only the very fittest of these little ones survived. The two Johns set a dreadful example to their children and are regularly in trouble with the authorities, the abuse of drink playing no small part in their downfall. Most of the offences they committed were petty ones – drunkenness and disorderly conduct in the town are their standard offences. There is a bizarre one of being charged with not paying a Library rate tax of just a few pence but still letting that end up in a court appearance. A more serious offence is committed in October 1864 when they are jointly charged with stealing three hens and a cock from a John Fish, a fellow weaver who lived higher up the town at a place called Stoney Flats on the road out towards Bolton. For this misdemeanour they received one month imprisonment at Preston. They count themselves to be fortunate not to have lived around forty years earlier. Back then they could have gone to the gallows.

John Atherton’s behaviour, despite having a large family to care for, sadly does not improve with age or maturity. In March 1868 he is back in Preston prison, this time for three months after being found guilty of threatening behaviour towards a woman in Darwen – Sarah Ann Bentley. This is a woman already known to himself and John Lowe, Sarah having grown up next to the Lowe family in Edgeworth, a few miles from Darwen. The pattern of irresponsible and reckless behaviour emanating from John’s father Abraham Livesey continues unfortunately with the next generation, especially with John’s son James Atherton, and this event will split the family apart because of its seriousness.

My great grandfather is also named John Atherton. He is born in Darwen in 1885 and at last he appears to break the mould of the Atherton male, living a respectable and responsible life without getting into any trouble with the law. He finds employment in the new Paper Mills that Darwen becomes famous for. My father also goes on to spend the majority of his working life at Belgrave Paper Mill in Darwen. The Atherton family situation through John begins to improve. There is never cream with the cake but the unbearable, relentless poverty of the Atherton clan thus far, starts to be alleviated at last. However, the family has much to go through before that comes to fruition and none of it is pleasant.

John Atherton and Margaret have their final children in 1885, my great grandfather John and his twin sister Margaret. Both babies are baptized at Holy Trinity Church in Darwen, but sadly Margaret does not live to reach her first birthday. On such fine margins do our lives today hang, John survived, and I am here to tell the tale. The family at the time still inhabit a dwelling on Water Street. Their abject poverty and low paid employment means that there is little chance of extricating themselves from this squalor.

By October 1890 both the Lowe and Atherton families are living in the same house in Water Street. How they made space in such a property is remarkable. The Athertons have been forced to vacate their property and the Lowes had taken them in, but where they all slept is difficult to say, but beds no doubt have to be shared. John Lowe, now a widow after the death of John’s sister has only two children at home; Nancy aged 18- and 23-year-old Jane. Jane however is now married. Incredibly her husband Robert Brindle also lives in the house with their three very young children. The family circumstance in that slum dwelling in Water Street we can only attempt to visualize, but nothing we can imagine will compare with the reality of that situation. The younger daughter Nancy looks after the three young children of her sister while Robert Brindle works full days in the paper mill as Jane heads off for her employment in the cotton mill. Her father John Lowe is also now employed in the paper mill which means that during the day Nancy is left alone in the house with the infant children.

So it is that late one afternoon towards the end of October 1890 Nancy is comforting the youngest child. She does not hear someone entering through the always open front door of 26 Water Street. She is grabbed firmly from behind, thrown down to the stone floor of the kitchen and indecently assaulted by the intruder. Before the situation becomes more serious for her, the attacker is disturbed by a passer-by hearing her screams. Nancy is left shaken and upset on the floor, but fortunately not seriously injured. Fleeing down Water Street, through the back alleyways and across the busy main road of Duckworth Street, desperate to evade capture, is her first cousin James Atherton. From being merely a youngster who is in regular trouble with the police on matters that can in the main be described as petty and delinquent, James is now in very serious trouble. Not only that, but he has also breached the trust in the family circle and that will have long term repercussions for himself and his father and siblings. Darwen is a small town and James is quickly apprehended behind the terraced housing near to the stinking polluted River Darwen and taken into custody. He appears before the town magistrates the next day, but they are unable to deal with such a serious case. James is sent for trial at Manchester Assizes, being incarcerated in Strangeways Prison in the centre of the city.

James does not have long to wait for his trial being brought before a jury at Manchester Crown Court on Wednesday the 19th of November 1890 and swiftly found guilty by the jury of ‘assault with intent to ravish’. The outcome for James seems surprising when looking back from our day as the sentence seems fairly lenient. He is given six months in prison, which he serves as most Athertons seem to do at the bleak Preston prison. For James, the actual sentence by the judge, although short, was to be for life as far as his extended family and the community surrounding him in Darwen were concerned. He has crossed a forbidden unspoken line and there is to be no going back. Of course, the family could in theory have just covered up the incident and not gone ahead with seeing James being prosecuted but for John Lowe his daughter’s honour came before family consideration. So, the extended family was torn apart.

After his arrest, the family are forced to move out of the Lowe property and his father is offered a small dwelling just off Tockholes Road at the back of Rock Terrace. This is next door to his son Jonathan, who is by now married and producing many children, of whom all but one die in infancy. They may have finally been out of the slum of Water Street, but this is a squalid existence in very poor, damp, cramped housing, with no modern facilities whatsoever. After his release from Preston prison, James initially goes back to this house, but it is clear that his life in and around his family in Darwen would be uncomfortable to say the least. The Lowe family have a daughter that James assaulted. Another has made a good marriage, and her new Brindle family would become respectable citizens in the town. In fact, one of their sons Sidney Brindle would become a physiotherapist specialising in sports injuries and he once treated me after a cricket injury. I had no knowledge that we were related until doing the research for this book. It is a small world as we will amazingly discover at the conclusion of the book.

It was clear to James Atherton that he has to change the course of his life. For him to stay in Darwen is impossible, the publicity his actions have generated both from the local news and gossip, combined with the denunciation by the Lowe family, means a daily living hell for him. He has no real skills as regards being able to make a living. He does not have the resources to move elsewhere in the country and set up a new home, so the only possibility he feels is available to him is to enlist into the regular army. He has stuck it out in the town for just over 12 months, but he decides that he has to make a move. He enlists for a long twelve years in total in the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment at Deepdale Barracks Preston on the 6th of December 1892.

That day, the one question on the form that causes him to squirm is when Regimental Sergeant John Gaffney asks him if he has ever been to prison for any reason. Firmly James answers – NO. This despite the fact that just at the other end of Deepdale Road, going past Preston North End football ground, is the forbidding outline of Preston Prison – a place that is well known to James and where he is well known to the staff. He gets away with the deception and as Private 3935 James Atherton he embarks on an adventure of a lifetime. One that ultimately will change his life forever, taking him to undreamed of faraway places, ultimately it will lead to a new civilian life in America. James is a small man, as is usual with most Atherton men, standing just 5 feet 4 inches tall. At 124 pounds in weight and with a chest measurement of 33 inches he will have to work hard to impress. In physicality he is a very slight man. He has however red hair, again an Atherton trait, and surely, we must take this as an indicator of the temperament that had led him into so much trouble. There are physical traces of that trouble with his facial scar and also the tattoos on both arms, unusual for the time for one that had not already served in the forces. He is passed fit and there can be no doubt that James, although small in stature, is a strong, hard man.

James Atherton as we now know had a troubled past and was frequently in trouble with the local police up until his imprisonment for the attempted rape of his cousin in Darwen at the home the two families shared. He also was brought up by his family in dreadful poverty and would have seen the army as a way out of this hopeless future in his hometown. However, it was his imprisonment for such a dreadful offence, one of such gravity that it could not be overlooked in the community or indeed within the family, which forced his hand to change direction. James has never been overseas; in fact, he has never even been out of his home county of Lancashire before. The farthest he had travelled was an involuntary trip by train at Her Majesty’s pleasure to his stay at Preston Prison.

This was soon to change and on the 27th of November 1893 he set sail with his regiment to Malta, a familiar and a popular posting for soldiers in the British Army. The island of Malta is very strategically placed and became even more so in the Second World War when the island suffered sustained bombardment from the Germans and their allies resulting in the awarding of the medal that is synonymous with the island. James is stationed in the garrison in Malta for almost three years and is promoted to be a Lance Corporal but for unknown reasons he quickly resigns that commission and returns to the ranks. The army has however brought a maturity to him that he could not have gained back in Darwen. He is a useful and effective soldier now, his doubtful past receding into the distance. It continues to go farther away from him as the regiment moves on to Ceylon, another long and difficult sea journey. Here in the very hot and humid climate of Ceylon he is stationed for another three years. It would be fair to say that the climate here is not suited to a northern constitution, Malta was much more preferable, but James endures all that this country can throw at him. It is not his favourite place in the world to be, it is uncomfortable, and he almost wishes he could feel the cold rain of Lancashire on his face.

However, he is nearing the end of his seven years as one of the Regulars and by the December of 1899 he knows he will be home but then will also have the difficult task of making his way back in civilian life. It is not to be, conflict is brewing in South Africa as the Government is drawn by events, partly out of their control, into a war that will define that part of the continent for many decades. It starts the decline of the Empire and any goodwill that may have surrounded it. The North Lancashire Regiment and 3935 Private James Atherton set out on their way to fight the Boers and maintain the vital access to the mineral deposits that the Empire needs and covets in the Free States the Boers are determined to keep full control over. Accompanying James on the voyage is his friend 5284 Private Samuel Hall who came to join up with the regiment in Ceylon towards the end of 1897.

The two young men quickly bonded, and that friendship would lead from the tragedy to come in South Africa to James eventual future marriage and his passport out of England for good. The arrival date of the ship of 11th February in Cape Town is significant as it will be twelve months to that very day when Samuel would be killed in a skirmish with Boers outside of Kimberley. James will leave with a medal for the defence of Kimberley and have to comfort the grieving family of his friend. James Atherton and his friend Samuel Hall have a dramatic start to the campaign in South Africa. You could say that they definitely drew the short straw as regards posting as they were immediately on arrival sent to the town of Kimberley, a strategically vitally important town that was famous for the wealth to be gained from the minerals but especially from the diamond mines in and around that area. They were soon followed into Kimberley by the mounted Infantry of the North Lancashire Regiment.

Once there, the North Lancashire soldiers along with other supporting regiments were put under the command of General Kekewich who also had assisting him a force of many local troops and members of the Police force. The General was grateful for the essential presence of the North Lancashire Regiments as they were able to get the defensive works of the town properly fortified. Because of the discipline of these Regiments, they raised the morale and the effectiveness of the hastily formed local forces to a very great degree. The full story of the defence of Kimberley is modestly dealt with by General Kekewich in his reports, but the fact is this small number of forces somehow managed to hold on during the siege from the Boer forces from 12th October to 15th February and kept 40000 inhabitants relatively safe – an astonishing feat in view of the odds ranged against them. The town fortunately was well supplied with provisions except for a scarcity of vegetables. The cattle that grazed around the town had been slaughtered and stored for food in refrigeration plants ingeniously constructed in the mines. Kekewich handled the situation with a very cool head and especially in his dealings with Cecil Rhodes, a difficult and arrogant man who had in effect started the conflict with his ludicrous goading of the Boers and now made his base with his entourage in Kimberley in an attempt to force the British to concentrate their efforts on this place that was materially beneficial to him.

James Atherton would know little of his commanding officer’s problems of a stressful political nature, but he did along with the other soldiers in the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment keep safeguarding the discipline required among the soldiers and civilians to withstand the long siege. The situation in the town did get quite desperate towards the end of the siege but relief was on its way in the shape of the mounted cavalry let by Major General John French, a name that would resonate through history with his later role in the First World War. Virtually all the British cavalry units in the region were massed together to carry out the relief of Kimberley, this was one of the largest concentrations of cavalry ever put together in history. Sunday February 11th, 1900 was the day that these troops made a significant breakthrough on the relief of Kimberley and sadly it was the day that Samuel Hall lost his life on an operation that had his friend James Atherton alongside him. Samuel took the snipers bullet, and my relative James Atherton survived. The blow from this to James was great but he had to keep his discipline and maintain the morale of the besieged town. Finally, the way to Kimberley was open and French’s troops could get through at very great cost mainly to the horses who suffered terribly in the heat and the relentless pursuit of the objective.

James was brave and devoted to his duty during the siege but his mental state by this time was not good. He coped well with the reality that he was trapped in the town for months along with the rest of his fellow soldiers and civilians, but he found the death at close quarters of his friend Samuel Hall almost impossible to cope with. He got into trouble and because of his attempts to drown his troubles with drink he was unable to function as a soldier. Four days after the relief of Kimberley he was given 10 days in a military prison. This was a sad end to a period of service where he had shown that he had matured, but he soon recovered his composure and continued with good conduct in the regular army until the 4th of January 1904.

In defence of James, you would have to feel that it was unlikely that James was alone in mentally cracking under the pressure and the relief of the siege coming to an end. He was awarded the clasp and Medal for the Defence of Kimberley. James continued in dangerous combat in South Africa until December of the following year and was engaged in many more front-line operations against the Boers. A foe mainly under the command of General Louis Botha. Much of the time in the Transvaal would have involved days of arduous marching including a very long trek to Klerksdorp near to Johannesburg, an area that has great family significance as we shall discover.

James Atherton took part in crushing determined Boer resistance in February 1901 at Haartebeeestfontein and the Loyal North Lancs were mentioned again in despatches by Lord Kitchener to have ‘greatly distinguished themselves’. Six of their numbers were killed in this particular action. James, under the command of Lord Methuen, would have trekked endlessly around the Western Transvaal and engaged in many skirmishes with the stubborn Boers. Finally, his war came to an end and James was back home before Christmas 1901, but home in the shape of the town of Darwen was a difficult place.

There is a Memorial to the fallen British soldiers who died in Kimberley, South Africa, which was commissioned by Cecil Rhodes. It commemorates the 27 soldiers who lost their lives in the siege. That is a remarkably small number considering the bombardment they faced and the numbers in the town. So, in retrospect James was in a safer place numerically speaking.

James Atherton, as we know, survives the brutal Boer War conflict, and is finally discharged from the regular army in 1904. He has initially served the seven years that he had signed up for but because of the outbreak of war he has also been obliged to serve his agreed five years in Reserve. In reality he never has a break in his service to say that he ever became a reservist, events take those matters out of his hands. Ultimately, he has not totally finished with the armed forces and as events unfold in his life, he actually is enlisted into the US Army just two months before the end of World War 1. Of course he does not make it to France. Fortunately, he is swiftly demobbed. James has been away from Darwen for 12 years.

He has with him a medal, a very prestigious medal from his fighting in South Africa. He is a changed man and with this maturity he can make a fresh start in life. It is not going to be that simple however, as Darwen back then is still the close-knit community that he had left all those years before. Yes, people know about the Boer War, and it has affected the local people. There is a building, basically a tram stop, built as a memorial to the local men who volunteered for the South African campaign. James Atherton is not commemorated on that memorial as he was a regular soldier, but that seems very unfair. He was denied any recognition by his hometown. South Africa was distant though and what James has been through could not be comprehended by the local population. It passes them by, and they have their own problems and hardships. To expect them to be impressed by James exploits in the African continent is not going to happen. Darwen is not ready to accept him back as one of them, at least those who had been close to him were not.

His first task on returning home was to visit Samuel Hall’s parents and family to give details of their son and how he met his premature end so far away from home. Samuel had an unblemished record as a soldier and James would have been able to reassure his parents about the character of their son and how he performed under such severe pressure. Samuel’s body was not returned home so his parents and sisters could not grieve for him in the normal way. For James it was a bittersweet time as he made repeated visits to the Hall family when on leave from the army.

His love for Lydia Hall, Samuel’s sister grew. He wanted to marry her, but he also did not want to return to live in Darwen on a permanent basis. Being in the army suited him as it kept him away from the memories of his past and the people who were still hostile to him, including family members. Lydia, the strong-willed Irish girl, agreed to marry him. James and Lydia were married at St Peters Church, Darwen in July 1903, James dressed in full military uniform.

The woman James falls in love with at the home of his tragic friend Samuel Hall is a strong Irish girl – Lydia Hall. Lydia is not to be messed with and James knows that he has met more than his match. But she will turn out to be the ideal lifetime companion for him. Lydia will live to be close to 100 years old and outlive the younger James by some distance. She will bind this family together and make a real man out of James. Not just a physical man but one who will now take his responsibilities more seriously. James could become this man, but he cannot deal with the ghosts of his past in Darwen.

Even the happy event of the birth of his beloved daughter Bertha in 1904 cannot take his mind away from all the whispers and staring eyes, and not being able to be accepted back into the extended family. It is extremely hard to find work. He is a brave old soldier, but everyone is aware of his past life in the town and there can be no escape. As far as the people were concerned, James is not a man to be trusted. James’s father has died, and he is in need of a fresh start, so the family are to be found on the crowded Liverpool docks pushing their way forward, carrying their few possessions to go up onto the deck of the trans-Atlantic vessel Ivernia heading for Boston, Massachusetts, Lydia carrying six-year-old Bertha. They will never return.

There is a new life, although it is still a hard one that does not bring wealth and prosperity. In the area of New Bedford, Boston they are not in the abject poverty of Darwen, and people here treat them as they find them – a great relief to the family. Initially they are staying with Lydia’s other brother Ernest Hall and his wife Bertha, James and Lydia’s daughter having been named after her. The Halls had emigrated earlier in 1907 and settled in Myrtle Street, New Bedford, Bristol some miles south of Boston. Lydia’s mother had also come out with them and stayed in America. Now at last her only two children are with her, six others had sadly died including Samuel the army friend of James Atherton. James and Lydia soon find rented accommodation, moving around the area regularly into different rental properties. James is employed in the local New Bedford copper works. New Bedford is set on the coastline, with the harbour opening onto Buzzards Bay just up the coast east of Long Island. Back in Darwen James was familiar with the dreadful sight and smell of the polluted River Darwen where all manner of pollutants from the cotton and wallpaper mills are spewed out along with more general domestic waste (if you know what I mean). This did not change until relatively recent times.

I went to school in a building that straddled the river. A point of interest during the day to distract you from the lessons, was counting how many different colours the river changed to during the day. In New Bedford James would have felt quite at home. The copper works along with other heavy industry including coal, oil, and lead works plus the easy discharge into the river by boat builders and other types of waterfront industry make the harbour a much-polluted place, where no fish or marine life can survive. It also affects the health of the inhabitants of course but James accepts that he is a manual labourer. It is all he knows, and despite the conditions and lack of real health and safety policies, he has to stay and make his living here. He leaves a successful legacy with his grandchildren but for him and his children these are difficult and unpleasant conditions in which to live but even this is a massive step up from the conditions of East Lancashire. James and Lydia have two more children, Elizabeth born in 1913 and James in 1914 and both these children went on to serve in the US Army during the Second World War. Young James was discharged from the US Army after 18 months with his health and well-being badly affected by his war service. He had a troubled life, was separated from his wife, and gave his children a difficult childhood before his tragic early death at the age of 47.

Elizabeth also died at the relatively young age of 58 and had a complex family life, having a son from whom she was estranged as she was from the father. They are both buried in Military cemeteries in America. The family situation in America from then on improved and this branch of the Atherton family are in their various family relationships still happily based in the area. Sadly, the English born Bertha did not live to adulthood, dying in 1917 aged 12, not long after they had settled in the States. It has to be said that it is a sad story overall, but it is one of fighting against adversity and also fighting the background of your upbringing and the poor role models that were on offer. In that you have to feel that James succeeded but he certainly learnt the hard way, making many unnecessary mistakes along the way. He had, importantly for him, the strong-willed Irish girl Lydia to guide and support him along the way. Their love took them through the hard times and produced ultimately a successful family legacy in America.

My great grandfather had essentially the same upbringing as James, but he learnt lessons from others and did not go through so much self-inflicted suffering.

Taken from my book ‘A Bullet for Life‘

Hi,

I thoroughly enjoyed this article, not least because it made mention of my own ancestors. We are related! Lovely to meet you!

John Lowe and Mary Atherton are my 4th Great Grandparents. Their daughter Jane Lowe, who married Robert Brindle are my 3rd Great Grandparents. Their daughter, Mary married Henry Albert Woodburn who died young in WW1. After his death, Mary moved back into her parents house with her sons, Norman and Robert and according to the 1921 census their uncle – and Mary’s brother – Sydney Brindle was still living at home.

My Grandad (son of Norman Woodburn, also called Norman), had fond memories of his Brindle relatives and by all accounts, the two families were very close. I remember him mentioning that Sydney had links with Blackburn Rovers re. his sports physiotherapy, but not sure if this is true!

Again, great article, nice to see someone else interested in the history of Darwen, and a relative too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Molly-Anne Hi Thank you for contacting me and so glad you enjoyed the article. Our families had incredible hardships to contend with back in those late Victorian times. Incredible to think that they all survived so that we could be here really. The Lowes and the Atherton’s were closely related of course and living together for some time up until the incident with Nancy and James Atherton. John Lowe and John Atherton were partners in petty crime with both troubling the magistrates for most of their lives. John Atherton mainly in later life for drunkeness and visiting ‘houses of ill repute’ around Water Street. John Lowe is described in a case in 1882 as a notorious poacher. Fortunately for us eventually the families became a bit more law abiding. The women of the families must have had a dreadful life with these two – and lots of childbirth. I didn’t know the Woodburns as far as I know although having had a quick look one of them lived and died on Ivinson Road a few doors down from where I grew up, so I must have come across him for sure. The story about Sid Brindle will most likely be true. He certainly had involvment with Darwen Football Club and he was always the go-to physiotherapist in the area. Looking at Sid he would have been well in his 70s when I went to him for cricket injury treatment. He kept his practice going even after ‘retirement.’ His house and practice was at the junction of Victoria Street and Sudell Road, at the bottom of the hill. John Atherton’s son John was my great grandfather. His wife’s grandmother was also a Brindle. Not sure if they are connected with your line but might have a look at that. If I can help at all with any more info I am happy to do so. I no longer live in Darwen having moved to Somerset about seven years ago to watch our granddaughter grow up. Hope all is well with you and likely you have escaped the abject poverty of Water Street. Best wishes Neal (a cousin no less)

LikeLike